I’m happy to welcome another debunker to the family! Check out their website busting common myths about the Civil War.

Here’s what this month’s Smithsonian magazine had to say in their “Ask Smithsonian” section about this tiresome myth, one that is vigorously promoted by the descendants of John Hanson. (For details, see Myth #88)

Q: John Hanson was the president of the Confederation Congress before George Washington was elected. Why isn’t Hanson considered the father of our country?

A: There was a substantial difference between the office John Hanson held starting in 1781 and the office George Washington was elected to in 1789. Under the Articles of Confederation, state delegates met to create and enact policies. When its members chose a “president,” they were choosing someone to moderate their debates and oversee some of their correspondence. Hanson’s role did not matter much to the average American. Compare that with Washington’s role, which was an executive position, set apart from the legislative branch by the U.S. Constitution. Washington had a significant sphere of influence. He was also the ceremonial head of state, symbolizing the unity and power of the nation. Washington, of course, had already been revered as a great leader of the Continental Army during the American Revolution. Hanson held a leadership role in the Confederation Congress, but he did not lead the people of the nation. –Barbara Clark Smith, Curator of Social History, National Museum of American History

Myth #49 deals with the use of blue- or purple-colored paper to wrap sugar loaves. A fascinating article was recently brought to my attention, a scholarly piece written by paper conservator Irene Bruckle about the history of blue paper making. She clarifies many points that I could only vaguely address, including the use of woad, logwood, and indigo; how blue was less expensive to make than white, so often used for wrapping; and various common mordants and dying procedures. One relevant paragraph reads as follows:

The production of sugar paper is well documented in the early 17th century, when a Saxon papermaker sold 50 balesof bluesugarwrapping papertoan Amsterdam paper merchant. The first patent in the history of paper manufacture, issued in 1665 in England, concerned the production of sugar paper. The use of this typeof paper continued in many European countries at least until the second world war.nSugar mills even made their own wrapping paper in associated paper mills. Since the paper was mainly intended to protect the sugar cone from dust, it was not required to be strong, could be made from coarse, un-retted rags which were sharply beaten, and did not necessarily require sizing. Different varieties of sugar paper existed: light- and dark blue or purple paper, or double-sided paperconsistingofa light-colouredsheet couched onto a dark blue sheet. The blue or purple ‘Dutch paper’ was particularly famous for its quality.

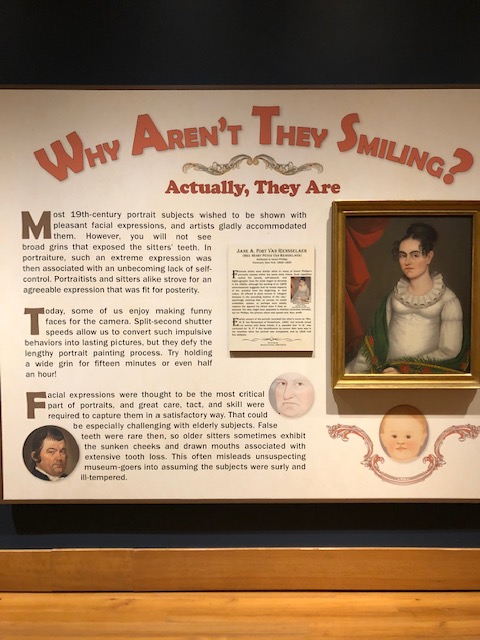

Colonial Williamsburg’s new decorative arts museum contains a section for the Folk Art collection as well as the colonial-era art and artifacts. When I last visited, I was amused to see the exhibit panel (above) about facial expressions in 19th-century portraits. Not surprisingly, it says much the same thing that I wrote in the book, DEATH BY PETTICOAT, and what I posted on this blog years ago about facial expressions in 19th-century photographs and portraits. Compare the two here.

Sadly, PETTICOAT was discontinued by Aramark, the company that now runs most of CW’s stores, restaurants, and hotels. I say “sadly” because the book had been well received and sold briskly in the museum’s shops; and it made a unique contribution to myth-busting in the history museum world. But PETTICOAT was hardly alone–most of CW’s educational books were discontinued by Aramark in the spirit of profit over education. You can still get a copy online.

During a recent visit to Colonial Williamsburg’s fine arts museum, I came across this panel about portraits with hands inside coats. Did painters charge less when one hand was hidden? Of course not. This was simply a popular, dignified pose for a gentleman and royalty of that era. Photographs of men often show this pose, and there was no question about saving money by hiding a hand in photography. See Myth #3 in this blog for more detail.

In a recent publication from the Smithsonian magazine, author Richard Grant debunks a long-held myth that was once promoted by the park service: that the Yellowstone region was a pristine wilderness, untouched by humans. Not true, says archaeologist Doug MacDonald. “Pretty much anywhere you’d want to pitch a tent, there are artifacts,” evidence of centuries of habitation by Native Americans. So why the myth? Find out in this interesting article (with lovely photographs). https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/lost-history-yellowstone-180976518/?utm_source=smithsoniandaily&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=20211229-daily-responsive&spMailingID=46175692&spUserID=ODcyNjc0Njc0MDg4S0&spJobID=2143332861&spReportId=MjE0MzMzMjg2MQS2

An impulsive visit to the Folk Art Museum in Williamsburg brought me face-to-face with examples from Death by Petticoat, the history myths book I wrote years ago for Colonial Williamsburg. Here’s some information about Myth #66 about itinerant portrait painters painting backgrounds first and adding the heads later. https://historymyths.wordpress.com/?s=66

For people who enjoy history myths, Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of an American Myth will be one of your favorite reads this year. I got it out of the library and was so impressed, I immediately bought 3 copies to give for Christmas presents.

Rightly called “historiography” rather than “history,” this book (by Bryan Burrough, Chris Tomlinson, and Jason Stanford) has two parts. It begins with a fascinating account of what historians actually know about the battle of the Alamo in 1836 versus the myths that have grown up over the decades. Believe you me, the truth is far stranger than fiction. The second half traces the crafting of the myths that, sadly, overtook the truth, which is far more interesting than John Wayne’s movie version.

As a writer who has tried HARD for forty years to make history enjoyable and engaging, I have to bow to my superiors. I read with envy their charming, conversational writing style, which made it feel as if they were talking directly to me. I laughed out loud any number of times. Trust me, you’ll find this book hard to put down.

Lisa Hassler, a Massachusetts realtor specializing in selling historic homes, wrote, “I was reading your blog and I couldn’t find any reference to wide plank floors, so I thought I’d ask. Many times, when visiting a house museum, the curator will say that the floor boards were “King’s wood” or “King’s lumber” because anything wider than X (I think 24”) was supposed to be sent back to England for the King’s use as ship’s masts. If that was true, then breaking the law was the norm rather than the exception. Would love to know, is King’s wood truth or fiction?”

Well . . . a little of both. Call it a stretch. Certain tall straight trees, especially Eastern white pine, could be marked with a Broad Arrow (three slashes) to reserve them for the monarch because they were so vital to making ship’s masts and booms. (Andrew Vietze, White Pine: American History and the Tree that Made a Nation) But this didn’t apply to all large trees or to all colonies. People using wide pieces of lumber for floorboards were not necessarily breaking the law or stealing the king’s lumber. Large, old-growth trees were plentiful in the early colonial years and widely used in furniture making and building.

Here’s where the 24″ part comes in. In Massachusetts, the Charter of 1691 states in part, “And lastly for the better provideing and furnishing of Masts for Our Royall Navy Wee doe hereby reserve to Vs Our Heires and Successors all Trees of the Diameter of Twenty Four Inches and upwards of Twelve Inches from the ground growing vpon any soyle or Tract of Land within Our said Province or Territory not heretofore granted to any private persons And Wee doe restrains and forbid all persons whatsoever from felling cutting or destroying any such Trees without the Royall Lycence of Vs Our Heires and Successors first had and obteyned vpon penalty of Forfeiting One Hundred Pounds sterling vnto Ous Our Heires and Successors for every such Tree soe felled cult or destroyed without such Lycence had and obteyned in that behalfe any thing in.” (Note the phrase: growing upon any soil or land . . . not heretofore granted to any private persons.)

In New Hampshire, an act passed in 1708 reserved all mast trees with a diameter greater than 24″ for the royal navy. Violators faced a fine of fifty pounds. In 1722 a new law reduced the diameter 12″. Surveyors of the King’s Woods were assigned to identify suitable mast pines with a broad arrow mark. (see http://www.NewEnglandHistoricalSociety.com, New Hampshire Pine Tree Riot of 1772, and https://websterhistoricalsociety.org/?p=309)

I wasn’t able to find similar laws in other American colonies.

However, it was definitely illegal to sell mast trees to anyone but the British navy, even though they paid less than the French or Spanish. That was a law colonists must have broken all too often, because Parliament kept passing laws protecting mast trees for the British navy.

The perfect book for me, right? This new (2020) book, Prohibition’s Greatest Myths, combines two of my main interests: history myths and the Roaring Twenties. It’s a small book, only about 150 pages, with ten essays by ten scholars (historians with a couple of sociologists and political science professors thrown in for good measure) that purport to reveal “the distilled truth about America’s anti-alcohol crusade.” A good debunking, right? Wrong.

What I found was a bit different. The only myth actually debunked was #5: Alcohol Consumption Increased during the Prohibition Era. Alcohol consumption did not increase. It declined quite a bit in the first years then gradually rose, but even after Prohibition’s repeal in 1933, people drank less on average than before. Not until the 1970s did alcohol consumption rise to pre-Prohibition levels. Okay, good debunking job.

The other nine essays serve merely to show that the statement (called a myth) is an accurate generalization that becomes more complex when one digs deeper. Which we could say about any generalization. That’s what generalizations are for. For example, in the essay “Prohibition Started Organized Crime” I read that there was some manner of organization in crime before Prohibition, but Prohibition “provided an unparalleled opportunity for expansion and development of such crime.” Sure. But generally speaking, Prohibition marked the explosion of organized crime like nothing that had ever been seen. In another example, the author intending to debunk the myth that “Religious Conservatives Spearheaded the Prohibition Movement” says it is “only partially true.” The movement appealed to more than just religious conservatives. The religious conservatives who led the movement in the early 19th century “were evangelical Christians of course” but their motives were different than modern Christian fundamentalists. Okay, but they’re still religious conservatives leading the movement. It’s a valid generalization.

The essays were interesting. It is the title that misleads. These aren’t myths that are debunked. These are valid generalizations that are explored in greater depth. But perhaps Prohibition Generalizations Explored in Greater Depth wouldn’t be as appealing a title.